Classic Games

This note will be consistently updated.

Prisoner’s Dilemma

Two members of a criminal organization are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge, but they have enough to convict both on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the ot her by remaining silent.

Poundstone, William. Prisoner’s dilemma: John von Neumann, game theory, and the puzzle of the bomb. Anchor, 1993.

Normal form

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate (Deny) | Defect (Confess) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate (Deny) | $b,b$ | $d,a$ |

| Defect (Confess) | $a,d$ | $c,c$ |

$a \gt b \gt c \gt d$.

If both cooperate, each gets R (for Reward). If both defect, each gets P (for Punishment). If one defects and the other cooperates, the defector gets T (for Temptation) and the cooperator gets S (for Sucker’s payoff).

In some studies, $a,b,c$ and $d$ are represented by $T,R,P$ and $S$ respectively.

- $T$: Temptation

- $R$: Reward

- $P$: Punishment

- $S$: Sucker’s payoff

Attractor of player1: Reversed N-like (or N-like)

| $b\downarrow$ | $d\downarrow$ |

|---|---|

| $a$ | $c(\nwarrow)$ |

Attractor of player2:

| $b\rightarrow$ | $a$ |

|---|---|

| $d\rightarrow$ | $c(\nwarrow)$ |

The “confess” action is the dominant one.

Nash equilibrium

Can be found by iterated elimination of strictly dominated strategies (IESDS). For player1: check the 1st num up-and-down. For player2: check 2nd num left-and-right.

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate (Deny) | Defect (Confess) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate (Deny) | $b(\downarrow),b(\rightarrow)$ | $d(\downarrow),a(\checkmark)$ |

| Defect (Confess) | $a(\checkmark),d(\rightarrow)$ | $c(\checkmark),c(\checkmark)$ |

Pareto optimal

(check 3 times for each state)

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate (Deny) | Defect (Confess) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate (Deny) | $b,b\ldots (\checkmark)$ | $d,a\ldots (\checkmark)$ |

| Defect (Confess) | $a,d\ldots (\checkmark)$ | $c,c \ldots(\nwarrow)$ |

Stag Hunt

In the simple, matrix-form, two-player Stag Hunt each player makes a choice between a risky action (hunt the stag) and a safe action (forage for mushrooms). Foraging for mushrooms always yields a safe payoff while hunting yields a high payoff if the other player also hunts but a very low payoff if one shows up to hunt alone.

- Peysakhovich, Alexander, and Adam Lerer. “Prosocial Learning Agents Solve Generalized Stag Hunts Better than Selfish Ones.” Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems. 2018.

- Harsanyi, John C., and Reinhard Selten. “A general theory of equilibrium selection in games.” MIT Press Books 1 (1988).

Stag Hunt is an Assurance Game.

Normal form

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate (Hunt) | Defect (Forage) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate (Hunt) | $a,a$ | $d,b$ |

| Defect (Forage) | $b,d$ | $c,c$ |

$a \gt b \ge c \gt d$.

Attractor of player1: Reversed u-like (or n-like)

| $a$ | $d\downarrow$ |

|---|---|

| $b\uparrow$ | $c(\leftarrow)$ |

Attractor of player2:

| $a$ | $b\leftarrow$ |

|---|---|

| $d\rightarrow$ | $c(\uparrow)$ |

Nash equilibrium

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate (Hunt) | Defect (Forage) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate (Hunt) | $a(\checkmark),a(\checkmark)$ | $d(\downarrow),b(\leftarrow)$ |

| Defect (Forage) | $b(\uparrow),d(\rightarrow)$ | $c(\checkmark),c(\checkmark)$ |

Pareto optimal

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate (Hunt) | Defect (Forage) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate (Hunt) | $a,a\ldots(\checkmark)$ | $d,b\ldots(\leftarrow)$ |

| Defect (Forage) | $b,d\ldots(\uparrow)$ | $c,c\ldots(\nwarrow)$ |

Snowdrift

The name Snowdrift game refers to the situation of two drivers caught with their cars in a snow drift. If they want to get home, they have to clear a path. The fairest solution would be for both of them to start shoveling (we assume that both have a shovel in their trunk). But suppose that one of them stubbornly refuses to dig. The other driver could do the same, but this would mean sitting through a cold night. It is better to shovel a path clear, even if the shirker can profit from it without lifting a finger.

Sigmund, Karl. The calculus of selfishness. Princeton University Press, 2010.

This game has the same payoff pattern as the games Chicken and Hawk–Dove. Alternatively, I could say that these two games share the same potential game?

Normal form

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate | Defect |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | $b,b$ | $c,a$ |

| Defect | $a,c$ | $d,d$ |

$a \gt b \gt c \gt d$.

Attractor of player1: Reversed n-like (or u-like)

| $b\downarrow$ | $c(\leftarrow)$ |

|---|---|

| $a$ | $d\uparrow$ |

Attractor of player2:

| $b\rightarrow$ | $a$ |

|---|---|

| $c(\uparrow)$ | $d\leftarrow$ |

Nash equilibrium

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate | Defect |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | $b(\downarrow),b(\rightarrow)$ | $c(\checkmark),a(\checkmark)$ |

| Defect | $a(\checkmark),c(\checkmark)$ | $d(\uparrow),d(\leftarrow)$ |

Pareto optimal

| Player1\Player2 | Cooperate | Defect |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | $b,b\ldots(\checkmark)$ | $c,a\ldots(\checkmark)$ |

| Defect | $a,c\ldots(\checkmark)$ | $d,d\ldots(\leftarrow\nwarrow\uparrow)$ |

Battle of the Sexes

Also known as Bach or Stravinsky.

Normal form

| Player1\Player2 | Bach | Stravinsky |

|---|---|---|

| Bach | $2,1$ | $0,0$ |

| Stravinsky | $0,0$ | $1,2$ |

Nash equilibrium

| Player1\Player2 | Bach | Stravinsky |

|---|---|---|

| Bach | $2(\checkmark),1(\checkmark)$ | $0(\downarrow),0(\leftarrow)$ |

| Stravinsky | $0(\uparrow),(\rightarrow)0$ | $1(\checkmark),2(\checkmark)$ |

Mixed strategy Nash equilibrium

| policy | q | 1-q | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Player1\Player2 | Bach | Stravinsky | |

| p | Bach | $2,1$ | $0,0$ |

| 1-p | Stravinsky | $0,0$ | $1,2$ |

If player1 chooses “Bach”, its expected payoff is

\[\mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Bach}\right) = 2q + 0\cdot (1-q) = 2q.\]And if it chooses “Stravinsky”, its expected payoff is $(1-q)$. It should be indifferent about playing heads or tails, otherwise it can improve its expected payoff by increasing the probability of the action that causes higher expected payoff. In this way,

\[\begin{aligned} \quad & \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Bach}\right) = \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Stravinsky}\right) \\ \Rightarrow \quad & 2q = 1-q \\ \Rightarrow \quad & q = 1/3 \end{aligned}\]If player2 chooses “Bach”, its expected payoff is

\[\mathbb{E}\left(r^2\mid a^2 = \text{Bach}\right) = p.\]And if it chooses “Stravinsky”, its expected payoff is $(2-2p)$. It should be indifferent about playing heads or tails, otherwise it can improve its expected payoff by increasing the probability of the action that causes higher expected payoff. In this way,

\[\begin{aligned} \quad & \mathbb{E}\left(r^2\mid a^2 = \text{Bach}\right) = \mathbb{E}\left(r^2\mid a^2 = \text{Stravinsky}\right) \\ \Rightarrow \quad & p = 2-2p \\ \Rightarrow \quad & p = 2/3 \end{aligned}\]The outcome is

| policy | 1/3 | 2/3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Player1\Player2 | Bach | Stravinsky | |

| 2/3 | Bach | $2,1$ | $0,0$ |

| 1/3 | Stravinsky | $0,0$ | $1,2$ |

And this outcome is worse than any of the pure strategy equilibria.

Introducing a Trusted Authority

Matching Pennies

It is zero-sum (at each entry). Players are fully competitive.

Normal form

| Player1\Player2 | Heads | Tails |

|---|---|---|

| Heads | $1,-1$ | $-1,1$ |

| Tails | $-1,1$ | $1,-1$ |

Mixed strategy Nash equilibrium

No pure strategy works.

| policy | q | 1-q | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Player1\Player2 | Heads | Tails | |

| p | Heads | $1,-1$ | $-1,1$ |

| 1-p | Tails | $-1,1$ | $1,-1$ |

If player1 chooses “Heads”, its expected payoff is

\[\mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Heads}\right) = q + (-1)\cdot (1-q) = 2q-1.\]And if it chooses “Tails”, its expected payoff is $(-2q+1)$. It should be indifferent about playing heads or tails, otherwise it can improve its expected payoff by increasing the probability of the action that causes higher expected payoff. In this way,

\[\begin{aligned} \quad & \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Heads}\right) = \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Tails}\right) \\ \Rightarrow \quad & 2q-1 = -2q+1 \\ \Rightarrow \quad & q = 0.5 \end{aligned}\]Rock paper scissors

It is zero-sum (at each entry). Players are fully competitive.

Normal form

| Player1\Player2 | Rock | Paper | Scissors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock | $0,0$ | $-1,1$ | $1,-1$ |

| Paper | $1,-1$ | $0,0$ | $-1,1$ |

| Scissors | $-1,1$ | $1,-1$ | $0,0$ |

Nash equilibrium

No pure strategy works.

\[\begin{aligned} \quad & \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Rock}\right) = \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Paper}\right) = \mathbb{E}\left(r^1\mid a^1 = \text{Scissors}\right) \\ \Rightarrow \quad & q = \frac{1}{3}. \end{aligned}\]Muddy Children Puzzle

Check my other note: Dynamic Epistemic Logic.

Trust

- In the first stage, the Donor (or Investor) receives a certain endowment by the experimenter, and can decide whether or not to send a part of that sum to the Recipient (or Trustee), knowing that the amount will be tripled upon arrival: each euro spent by the Investor yields three euros on the Trustee’s account.

- In the second stage, the Trustee can return some of it to the Investor’s account, on a one-to-one basis: it costs one euro to the Trustee to increase the Investor’s account by one euro.

- This ends the game. Players know that they will not meet again.

Ultimatum

The experimenter assigns a certain sum, and the Proposer can offer a share of it to the Responder. If the Responder (who knows the sum) accepts, the sum is split accordingly between the two players, and the game is over. If the Responder declines, the experimenter withdraws the money. Again, the game is over: but this time, neither of the two players gets anything.

Braess’s Paradox

A computational example about Braess’s Paradox is in Figure 18.2 of this chapter:

Roughgarden, Tim. “Routing games.” Algorithmic game theory 18 (2007): 459-484.

Public Goods v.s. Common Recourses

These two kinds of games are social dilemmas, i.e., the situations in which individual actions that seem to be rational and in self-interest can lead to collective outcomes that are undesirable for everyone.

Public Goods Game

Setup

In this game, a group of players is each given a sum of money (or any resource). They are offered the choice to invest any portion of this sum into a common pool. This pool is then multiplied by a factor greater than one (but less than the number of players) and distributed evenly among all players, regardless of their individual contributions.

Dilemma

The group’s best outcome is if everyone contributes the maximum amount because this would result in the highest multiplication and distribution to everyone. However, from an individual’s perspective, the best strategy is to contribute nothing and free-ride on the contributions of others. If everyone thinks this way, no one contributes, and the group ends up worse off.

Examples

- The Snowdrift Game (or Hawk-Dove Game)

- The Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Common Resources Game (or the Tragedy of the Commons)

Setup

Players have access to a shared resource (like a common grazing field for sheep). Each player decides how many units of the resource (e.g., how many sheep) to use. The resource can regenerate over time, but if overused, it can get depleted.

Dilemma

If all players use the resource sustainably, the resource persists, benefiting everyone continuously. However, each player has an incentive to use as much of the resource as quickly as possible to gain immediate benefits, especially before others use it up. If all players act on this individual incentive, the shared resource gets depleted, and everyone ends up worse off in the long run.

Differences

- Nature of the Good:

- Public Goods: These are non-excludable (one person’s use doesn’t exclude another’s use) and non-rivalrous (use by one person doesn’t reduce its availability to others). Examples include clean air, national defense, and public parks.

- Common Resources: These are non-excludable but rivalrous. One person’s use directly impacts another person’s ability to use it. Examples include fisheries, forests, and shared pastures.

- Primary Challenge:

- Public Goods: The challenge is about contributing to the provision of the good. The temptation is to free-ride on others’ contributions.

- Common Resources: The challenge is about overuse and depletion of the resource. The temptation is to over-exploit before others do.

- Outcome of Selfish Behavior:

- Public Goods: If everyone acts selfishly, the public good is under-provided or not provided at all.

- Common Resources: If everyone acts selfishly, the common resource is quickly depleted, rendering it unavailable even for future use.

The Cooperative Game

Disambiguation

The canonical definition of the cooperative game in game theory is different from the current common sense of MARL.

Cooperative game theory deals with situations where players can benefit by cooperating, and binding agreements are possible. In these games, players form coalitions, and the outcomes depend on the behavior of these coalitions. The primary goal in cooperative games is often to understand how the gains from cooperation should be fairly distributed among the players.

Notably, a key difference between cooperative and non-cooperative game theory is the idea of commitment. In cooperative games, it’s assumed that players can make binding commitments to each other, whereas in non-cooperative games, players choose strategies without the possibility of making binding agreements.

Formal definition

Key elements of a cooperative game:

- Players: A finite set of players $N$.

- Value function: Given any subset $S$ of $N$ (a coalition), the value function $v: 2^N \to \mathbb{R}$ assigns a real number $v(S)$ representing the total value or utility that the coalition $S$ can achieve by cooperating. Note that $v(\emptyset) = 0$, meaning the value of an empty coalition is zero.

- Characteristic function form: Cooperative games often take this form, where for every subset $S$ of $N$, a value $v(S)$ is specified. The number $v(S)$ represents the payoff that the members of $S$ can guarantee by forming a coalition and excluding all other players.

An example: The “Airport Game”

Certainly! Let’s delve into a classic example of a cooperative game: The “Airport Game”.

Scenario: Imagine there are three airlines: A, B, and C. They are considering building a runway at a shared airport. Each airline can benefit from the runway, but they benefit differently based on the size of their planes and the number of flights they operate. They want to decide how much each should contribute to the construction costs.

- Airline A’s planes are large, and it would be willing to pay up to $600,000 for the runway if it had to bear all the costs itself.

- Airline B operates smaller planes and would only be willing to pay $300,000.

- Airline C operates the smallest planes and would pay just $100,000.

The total cost of the runway is $800,000.

Coalitional Values: If they cooperate, the total cost can be divided among them. The value each coalition (subset of airlines) can generate (or save) is as follows:

- $v(A) = 600,000$

- $v(B) = 300,000$

- $v(C) = 100,000$

- $v(A,B) = 800,000$ (since together they can cover the total cost)

- $v(A,C) = 700,000$

- $v(B,C) = 400,000$

- $v(A,B,C) = 800,000$ (since all three together can cover the total cost)

The question now becomes: How should the $800,000 cost be distributed among A, B, and C in a way that reflects their individual benefits and the benefit of their cooperation?

Solution Concepts: There are various ways to allocate the costs based on cooperative game solution concepts. One of the most famous methods is the Shapley value, which provides a unique way to fairly allocate the costs based on individual and collective benefits.

By computing the Shapley value for this game, one would find a fair division of the costs among A, B, and C.

Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma

Axelrod, Robert, and William D. Hamilton. “The evolution of cooperation.” science 211.4489 (1981): 1390-1396.

Successful strategy conditions

Stated by Axelrod. The following conditions are adapted from Wikipedia.

- Nice/optimistic: The strategy will not defect before its opponent does.

- Retaliating: The strategy must sometimes retaliate. Otherwise it will be exploited by the opponent.

- Forgiving: Though players will retaliate, they will cooperate again if the opponent does not continue to defect.

- Non-envious: The strategy must not strive to score more than the opponent.

Strategies

- Tit-for-tat.

- Win-stay, lose-switch.

- Zero-determinant strategy. (Check my other note.)

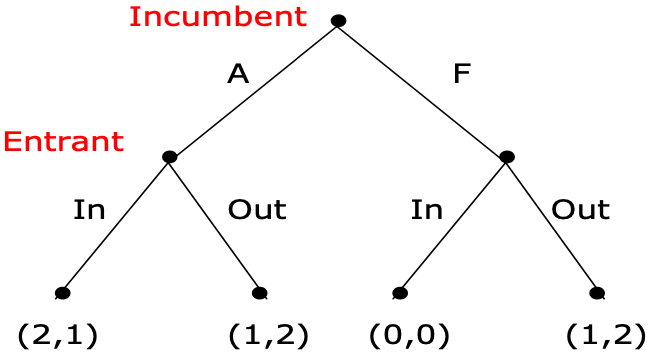

Entry Deterrence Game

- There are two players.

- Player 1, the entrant, can choose to enter the market or stay out. Player 2, the incumbent, after observing the action of the entrant, chooses to accommodate him or fight with him.

(From MIT 6.254 2010: Game Theory With Engineering Applications Lecture 12)

Nash Equilibrium

Equivalent strategic form representation:

| Entrant $\backslash$ Incumbent | Accommodate | Fight |

|---|---|---|

| In | $(2,1)$ | $(0,0)$ |

| Out | $(1,2)$ | $(1,2)$ |

Two pure Nash equilibria: (In,A) and (Out,F).

Subgame Perfect Equilibrium

The equilibrium (Out,F) is sustained by a noncredible threat of the monopolist. This Nash equilibrium means that the monopolist will bluff that “if you choose to be in, then I will choose fight.”

But by backward induction, we can see that (In, F) can be eliminated, since the monopolist will get more in (In, A).

So in the first depth of nodes, the entrant will choose to be in because in (In, A) it gets 2 while it gets 1 in (Out, F).

In this way, there is only one SPE, which is (In, A). The noncredible threat (Out, F) Nash equilibrium is eliminated.

The Value of Commitment

Exchanging the timing of agents, then the threat turns to be credible.

Entry Deterrence Game with Timing Exchanged.

Entry Deterrence Game with Timing Exchanged.

This implies that the incumbent can now commit to fighting. And it is straightforward to see that the unique SPE now involves the incumbent committing to fighting and the entrant not entering.

Disclaimer: The description of games is from Wikipedia and other sources (books or papers). Corresponding links or references have been provided. The content regarding attractors is my personal understanding.