Information Design in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

Resources

- Information Design in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning.

Yue Lin, Wenhao Li, Hongyuan Zha, Baoxiang Wang.

Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2023. Poster.[Paper] [Code] [Experiments] [Blog en] [Blog cn] [Zhihu cn] [Slides] [Talk en] [Talk RLChina]

Key Words: Information Design, Bayesian Persuasion, Sequential Social Dilemma, Multi Agents, Reinforcement Learning, Communication, Policy Gradient, Obedience Constraints, Bayesian Correlated Equilibrium.

What Do We Want: We want to design a model-free RL algorithm for the sender in a Markov sequential communication setting. This algorithm will enable the sender to utilize signals strategically, thereby manipulating the behavior of a receiver whose interests may not fully align with the sender’s. The ultimate goal is to optimize the sender’s own expected utility.

Focus

- Our Proposed Model: Markov Signaling Game (A Markov Model)

- Our Proposed Techniques: Signaling Gradient, Extended Obedience Constraints.

- Our Proposed Experimental Environment: Reaching Goals (A Sequential Social Dilemma)

- Highlights

- The sequential persuasion process is modeled as a Markov model.

- A sender and a receiver meet multiple times. Not a stream of receivers.

- The commitment assumption is canceled.

- The analysis analogous to the revelation principle is canceled.

- The receiver is a model-free RL agent, learning from scratch.

- The sender is also a model-free RL agent, learning from scratch. It does not know the environment model. It has no prior knowledge.

- We have tested our algorithm in challenging MARL sequential social dilemma.

- Our algorithm can use the Actor-Critic framework, which can make it incorporate modern RL techniques.

Here, the term “long-term” encompasses two perspectives:

The first perspective refers to the long-term aspect within each episode, where the receiver needs to consider long-term expected payoffs. This is because they do not receive rewards at every step but instead need to reach a goal to obtain a reward. This assumption, common in RL, represents a breakthrough in the context of economics’ information design. Previously, the focus was mainly on one-step scenarios or repeated game situations.

The second perspective of “long-term” pertains to the learning process itself. Not only do agents need to start from scratch in understanding the world, but they also need to build trust from the ground up. A key assumption in information design is the commitment assumption, justified by long-term interactions where the sender pays attention to maintaining their reputation (or credibility). The training process in RL actually simulates this long-term interactions, allowing us to directly dispense with the commitment assumption.

Preliminaries

- Information Design / Bayesian Persuasion [my blog]

- RL Basics:

- Markov Models

- Policy Gradient [my blog]

- MARL Communication: DIAL/RIAL

- MARL Mechanism Design: LIO

Markov Signaling Game

Definition

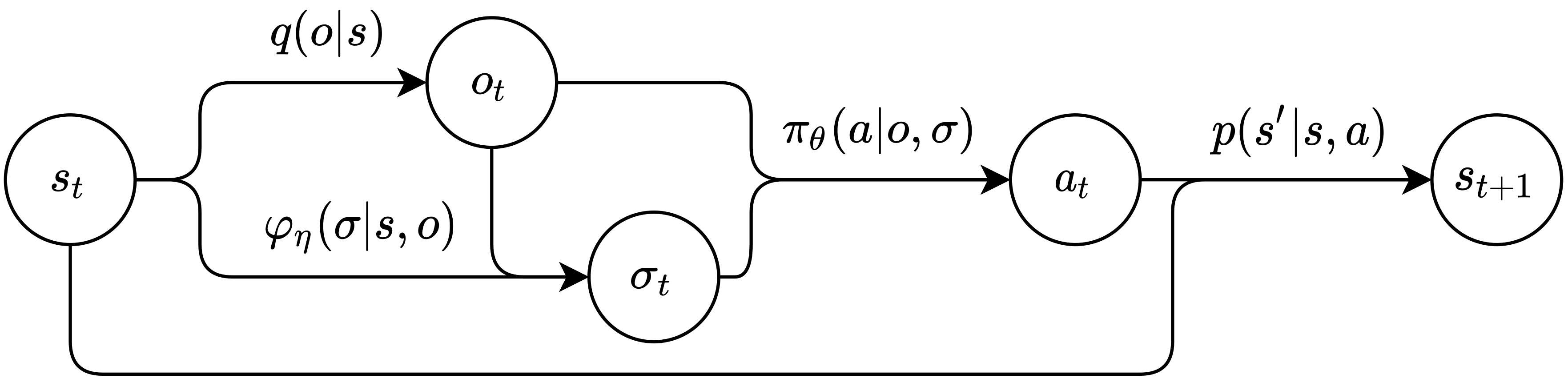

Illustration of the Markov signaling game. The arrows symbolize probability distributions, whereas the nodes denote the sampled variables.

Illustration of the Markov signaling game. The arrows symbolize probability distributions, whereas the nodes denote the sampled variables.

A Markov signaling game (MSG) is defined as a tuple \(\mathcal{G} = \left(\ i, j, S, O, \Sigma, A, R^i, R^j, p, q \ \right).\)

- $i$: The sender. The sender can only send messages, it cannot take the environment action, but it can access the global state.

- $j$: The receiver. The receiver can take environment actions, but it cannot see the full states.

- $S$: The state set. The state can only be seen by the sender. It is just like the state set in MDPs.

- $O$: The receiver’s observation set. The receiver’s observation can be seen by both agents. It is just like the state set in POMDPs.

- $q$: The emission function. $q: S\to O$.

- $\Sigma$: The sender’s signal set.

- $\varphi_{\eta}$: The sender’s stochastic signaling scheme. The sender sends messages based on the current state and the receiver’s current observation. $\varphi_{\eta}: S\times O \to \Delta(\Sigma)$.

- $A$: The receiver’s environment action set.

- $\pi_{\theta}$: The receiver’s stochastic action policy. The receiver takes actions based on the current observation and its currently received signal from the sender. $\pi_{\theta}:O \times\Sigma \to \Delta(A)$.

- $R^i$: The sender’s reward function. The reward is only dependent on the state and the receiver’s action. $R^i: S\times A\to\mathbb{R}$.

- $R^j$: The receiver’s reward function. $R^j: S\times A\to\mathbb{R}$.

- $p$: The state transition function. The transition of states is only dependent on the current state and the receiver’s action. $p: S\times A \to \Delta(S)$.

Note that:

- The sender can optimize its expected utility only by influencing what the receiver can see.

- There are two reward functions. The sender’s reward function can be different from the receiver’s. Thus they can be mixed-motive, not fully cooperative.

A constraint of MSGs: By the sender’s informational advantage of the problem setting, we assume that \(\set{s_t - o_t}_{t\ge 0}\) affects the receiver’s payoff. This ensures that the sender has information that the receiver wants to know but does not know. Thus the sender has the power to influence the receiver’s behavior.

And there are several extensions of MSGs, which are discussed in Appendix B.

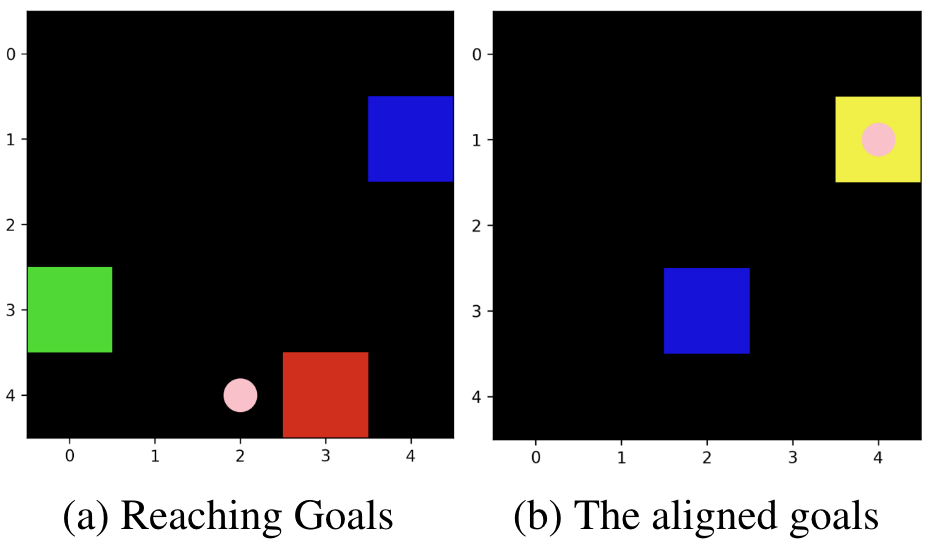

A Challenging Task: Reaching Goals

Imagine two selfish pirates sailing in a sea area on the same pirate ship, each wanting to go to their own island. One of them is the helmsman (the receiver) who can control the movement of the ship, but he only knows the absolute position of the ship and is unaware of the location of the island he wants to go to; the other is the navigator (the sender), who has a map and compass and can see the location of all the islands (both the island he wants to go to and the island the helmsman wants to go to), but he cannot control the movement of the ship. This task focuses on the navigator, aiming for him to learn an appropriate signaling pattern to persuade the helmsman, thereby indirectly controlling the ship to sail to the island he wishes to go to.

A possible solution is: the sender always directs the receiver to sail to the island he himself wants to go to, but if the ship is closer to the receiver’s island, they would make a detour there. Over time, the receiver would realize that this always yields more rewards than wandering aimlessly, hence he would follow the sender’s suggestions.

- The blue square: The receiver’s pirate ship.

- The sender is on the receiver’s pirate ship. Alternatively, you could say the sender is out of the region.

- The red square: The sender’s goal. If the receiver’s pirate ship reaches here, then the sender gets a positive reward.

- The green square: The receiver’s goal. If the receiver’s pirate ship reaches here, then it (the receiver) gets a positive reward.

- The yellow square: The red square and the green square overlapped, meaning that the goals of agents are aligned.

- The pink dots: The message sent by the sender.

Rules:

- The sender has a nautical map, it can see every object’s position.

- The receiver can only see its absolute position, by default. We have tested the influence of the receiver’s observability, as shown in Appendix H. The more the receiver can see, the less the informational advantage the sender has, the less the sender can manipulate.

- Only the receiver can steer the pirate ship. The receiver’s actions consist of moving

up,down,left, orrightby one square. - At any given time in the map, there is only one target goal for the sender and one for the receiver, both uniformly distributed and randomly generated.

- Once the receiver reaches a goal, it will be regenerated. And the regenerated goal and the receiver will not be in the same position.

- An episode will only end when the specified step limit is reached. Thus, making the receiver take a detour harms the receiver’s efficiency of reaching its goals, and thus harms its expected long-term payoff.

Why it is challenging:

- The sender cannot take environment actions. It can only influence what the receiver can see.

- When the receiver’s decision to pursue the green goal would mean moving away from the red goal. And in a fixed-length episode, this will reduce the receiver’s goal harvesting efficiency.

- Since the respawn locations of goals are randomly and uniformly distributed, the positions of goals are highly likely to be non-coincident. As the map size increases, the conflict of interest between the sender and the receiver increases.

Difficulties

From the Comparison to Economic Works

- The agents are both learning agents.

- The agents are model-free.

- It is a sequential persuasion problem. The problem is to solve a Markov model.

- The sender cannot make commitments.

From the RL View: Solving the Sender’s Optimization Problem on MSGs

There is a serious non-stationarity issue here.

The receiver is a solipsistic RL agent, meaning that it treats the observation and the signal as its environment. Thus, each time the sender updates its signaling scheme, the receiver’s environment changes, too. Because the distribution of signals (the receiver’s policy input) changes. In other words, the sender are designing the receiver’s solipsistic environment.

In this way, signals should not be simply viewed as a kind of action.

From the Learning View

It is hard for the sender to establish its credibility.

The agents are required to learn from scratch. In the beginning, their policies are nearly random. If the sender cannot find the proper signaling scheme efficiently, then its immature signaling scheme will make it lose the trust of the receiver. And this is a strong equilibrium, once reached, it cannot be exited.

From the MARL View

The two agents have mixed motives.

Currently, the mainstream of the MARL works focus on fully cooperative communications. Some other MARL papers use the term “mixed-motive” to describe scenarios involving two groups of agents, where agents within the same group cooperate but have conflicts with agents from the other group. While we use the term “mixed-motive” to describe the non-fully-cooperative-also-non-fully-competitive case between two agents.

From the Comparison to LIO

Information design is far more difficult than incentive design.

- Signals can be ignored. Incentives are compulsory. In the training beginning, the signaling scheme is almost random, the receiver will easily learn to ignore the messages, and this case is a strong equilibrium.

- Signals immediately change transitions (it affects both the sampling phase and the update phase of RL). Reward does not affect trajectory (it only affects the update phase of RL). So the hyper-gradient method used in LIO is not applicable here (the first-order gradient from the sampling phase is dominant).

- The sender cannot take environmental actions. It only can get feedback from the receiver’s actions. It is an indirect feedback flow.

Insights of Methods

Signaling Gradient

The sender is to optimize its expected utility in an MSG.

We can define value functions and Bellman equations in MSGs just like what we did in MDPs. Then the sender derives $\nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}\left[V^i(s_0)\right]$ in MSGs. We can expand the equations using Bellman equations, again, just like what we did in MDPs. And it can be easily seen that the gradient chain through the decision processes of both agents, meaning that the sender takes “its signal’s influence on the receiver’s policy through the Markov model” into account. And once we have finished the derivation of the gradient, we can get its unbiased estimation way.

Please kindly refer to the derivation of Policy Gradient first.

If the sender’s signal is treated as a kind of action, then its gradient will lose a part of the chains, and thus be biased.

Note that: Signaling Gradient is not only suitable for mixed-motive communication, but is also suitable for fully-cooperative communication. Because the derivation does not use any mixed-motive assumption.

Extended Obedience Constraints

Incentive compatibility in MSGs. The receiver’s policy is Markovian, not history-dependent. The receiver takes actions only based on its current received message, not including the previously received messages. At every timestep, it takes actions based on the current estimation of the future payoffs. So the obedience constraint can be easily extended in MSGs. So it can be easily adapted from the obedience constraints in Bayesian persuasion.

Applicable Scenarios

Applicable scenarios should contain these elements:

- Communication

- Mixed-Motive (Signaling Gradient with the Extended Constraints) or Fully Cooperative (Signaling Gradient)

- Informational Advantage: The sender should know something that the receiver does not know but wants to know.

- $o^i - o^j\ne \varnothing$,

- $o^i - o^j$ affects the receiver’s payoff expectation.

- The receiver is rational and risk-neutral, in a sense of RL.

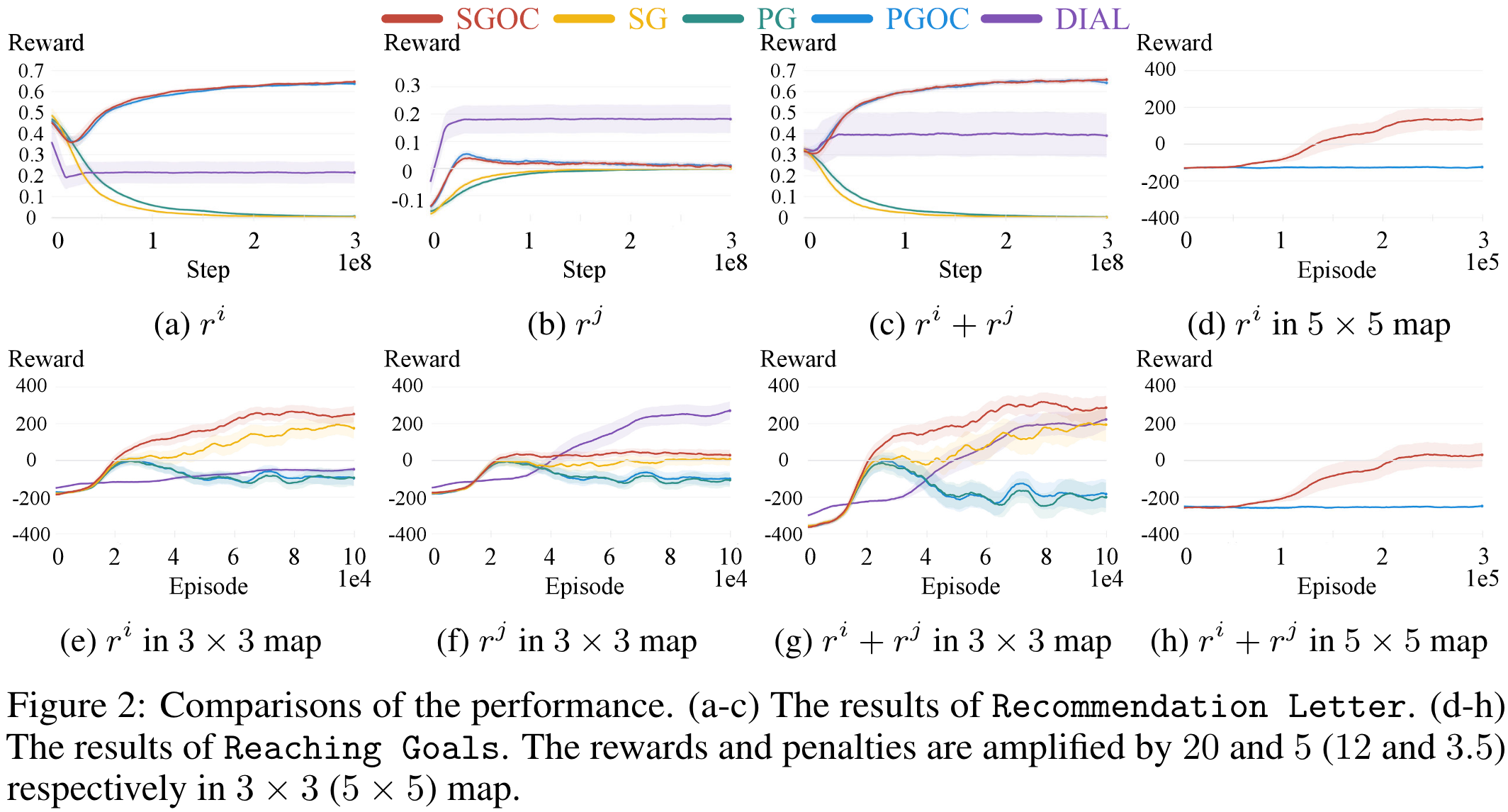

Interesting Experimental Results

Main Results

- In the simple Recommendation experiment, the extended obedience constraints improve the performance a lot.

- In the challenging Reaching Goals experiment, the Signaling Gradient improves the performance a lot.

- The DIAL sender is not concerned about itself at all.

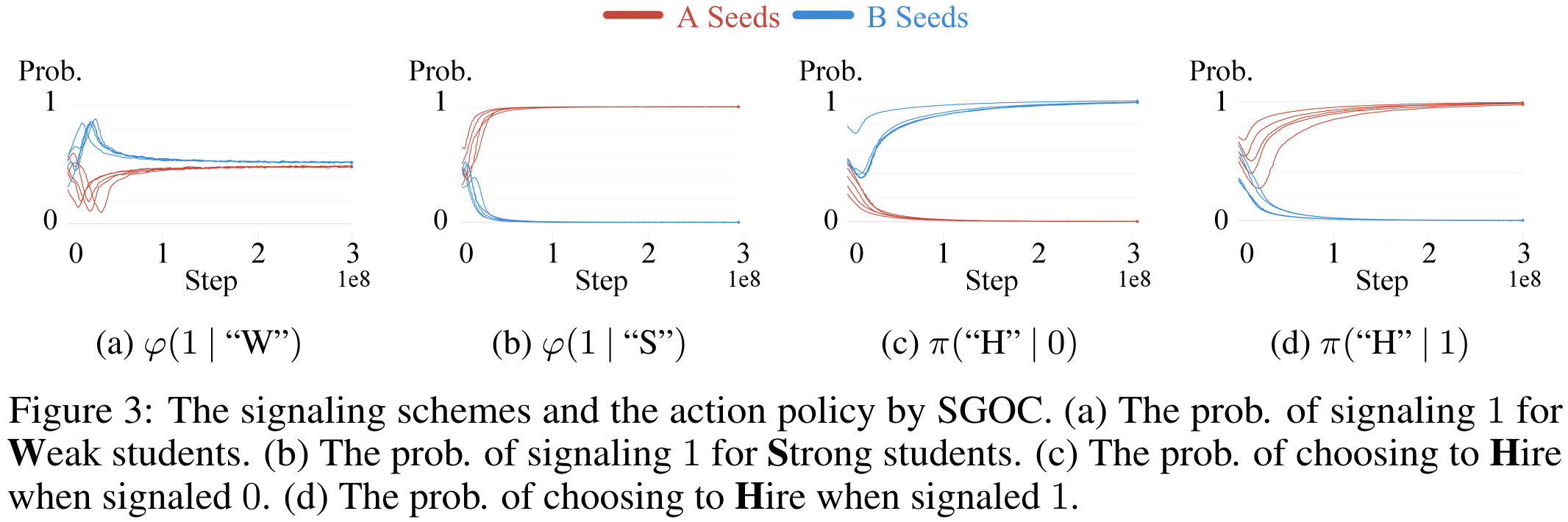

Symmetricity

There emerge different languages across different random seeds. As shown in Section 5.3.1.

The Honesty of the Sender

The honesty of the sender can be manipulated by the hyperparameters of the Lagrangian method, as shown in the heatmap in Appendix H.6.

The Observability of the Receiver

The more the receiver can see, the less the informational advantage the sender has, the less the sender can manipulate, as shown in Appendix H.

Gamma

In information design, if the receiver is far-sighted, the problem becomes very complex (discussed in section 4.5.3). In our experiments, we used a discounted reward factor of 0.1, and subsequent experiments have shown that it is fine when this value is between 0.1 and 0.8.